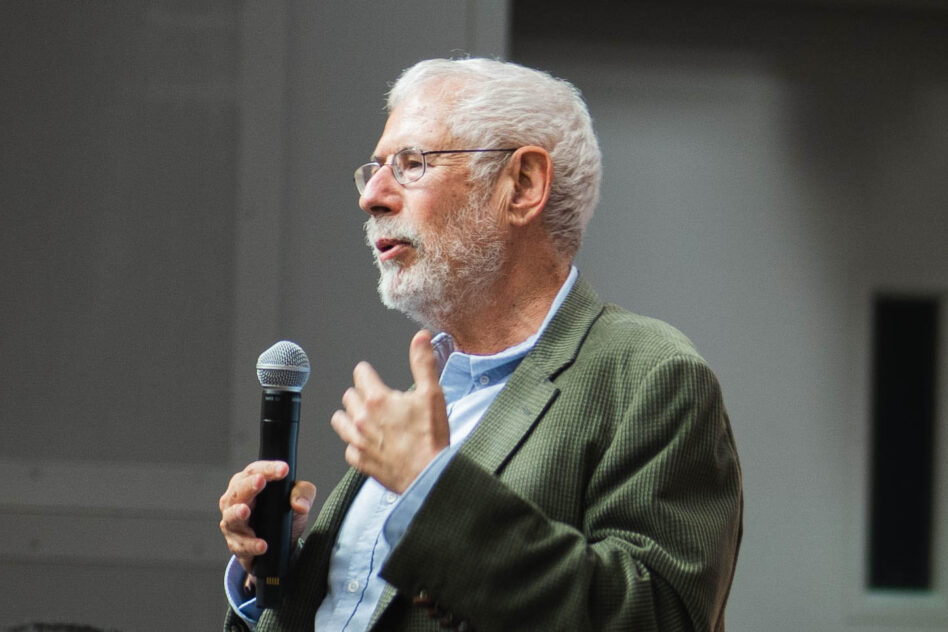

Chances are, if you’re interested in innovation, you’ve heard of Steve Blank. The entrepreneur, educator, and founding member of the Gordian Knot Center at Stanford University is a legend: he has built company after successful company and helped to develop the “Lean Startup” methodology based on his decades in Silicon Valley. If you’ve ever been told to employ iterative development or fail fast, it’s because of Blank.

In the last decade, however, he has looked towards the Pentagon. After Blank retired, he realized that everything he’d learned about building better companies could be applied to building a stronger and better military.

Hacking the Pentagon: In 2016, Blank founded the Hacking for Defense program at Stanford, which pairs students with the DoD to solve real, pressing military challenges. As the military has tried, slowly, to spur innovation, Blank has acted as an advisor to everyone from the DIU to the National Security Innovation Network (NSIN).

Making waves: Blank believes firmly in one simple truth: the way the Pentagon sets requirements and acquires weapons and software needs to change. Commercial companies have surged ahead of defense primes in terms of software and advanced technology development, and yet the military has failed to bring them into the fold. If the US wants to deter—or defeat—China, Blank says, the military needs to begin thinking a bit more like a startup.

Tectonic sat down with Blank to talk about his career, what the US needs to do to drive technological innovation and improve readiness, and how companies can succeed in working with the Pentagon.

Note: This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Tectonic: Why did you get into defense?

Steve Blank: My career started in defense. I spent four years in the Air Force during Vietnam in Southeast Asia and then did eight startups in Silicon Valley, and then when I retired, about 25 years ago, I started thinking about innovation entrepreneurship. Post-Snowden, I got a call back to help the government re-establish some of its innovation ecosystem. Then, I met Pete Newell and Joe Felter, two retired Army colonels. We took the design of my innovation classes for the National Science Foundation I-Corps and turned it into Hacking for Defense. So, the world kind of runs in circles.

What are the most important things you’ve learned about the defense tech industry since?

I learned things on two different ends. One is that the students of any generation are pulled towards mission-driven activities, whether it’s climate, or social justice, or in this case, national security.

While it’s clear to some of us that national security has been paramount regardless of the decade, I think the last five years of Ukraine, China and the Uyghurs, and Hong Kong have put a point on the fact that the world doesn’t work the way 21-year-olds think it should work. Unless you’re personally engaged, things may not come out the way you want them it to. That’s number one. Students are willing to engage in things that motivate them with passion and interest.

The other learning is that even experienced entrepreneurs who think that the government is nothing more than selling enterprise software will be profoundly surprised at the complexity of selling and scaling a defense business and they typically go out of business.

Historically, for new entrants, selling to the government was like the myth of Sisyphus, pushing that stone uphill and having it continually roll down on you. That’s changed for the better in the last few years and hopefully in this new administration, it’s going to radically change again, and hopefully, something like the FoRGED Act will change it yet again for the better.

What do you think needs to change in the Pentagon to encourage defense innovation and bring nontraditional defense companies through the door?

At the end of the day, it starts with the leadership, and then it flows down. There are a ton of entrepreneurs and innovators inside the department and in the defense and intelligence community, but there hasn’t really been a department-level understanding that, for the first time ever, the DoD no longer owns all the technologies or even the weapons systems needed to deter or win a war.

That has never before been true in the history of the United States. Today, Drones, semiconductors, AI, access to space, biotech, et cetera—all these things that are fundamental to modern weapons systems—there’s now more money, more people, more innovation, more speed and delivery going into those things outside the existing DoD infrastructure than inside.

Our entire Pentagon acquisition system is not oriented to buy from, learn from, or deal with this new class of external vendors. We built a great system to work with existing prime contractors: The top 10 or 20 get about 80% of all the defense contracts. It’s not that [people in the primes] are dumb, it’s not that they’re bad, it’s just that they can’t hire the best and the brightest because startups are paying baseball star salaries to AI engineers and drone folks. And [the primes] business model is not designed to do iterative and incremental innovation. It’s designed for change orders, long lead times, and waterfall engineering.

We can benchmark our progress against our potential adversaries. Look at the speed that China puts destroyers on the water, the innovation in drones that happens literally on a weekly basis, or the battlefield in Ukraine. There is no prime that is keeping up with that quantity.

Private capital, however, is pretty good at that. We just haven’t built a DoD acquisition system at scale that allows us to leverage its speed and energy.

The DoD has world-class organizations and world-class people, for a world that no longer exists. While it’s made small changes, it truly is an example of putting lipstick on a pig.

All the reforms make people inside the building think they’re doing something good to make the process better, but very few of them spend their lives outside the building understanding what the world looks like. Any time we take a senior national security official and put them on temporary duty inside a venture capital firm or startup, their head explodes.

You just can’t understand inside that five-sided building how fast things move in the commercial world.. You truly don’t have an appreciation of what the world has moved on to, and therefore you’re stuck in the same systems you have. It’s going to take some radical change to make that better.

Will that change actually happen? How much change do you expect we’ll see in the next four years?

The analogy I like to use is what happened in World War II. I want to remind everybody that a single professor, Vannevar Bush, the ex-dean of engineering of MIT, went to President Roosevelt in 1940 and said, “Listen, this upcoming war, which we eventually will be part of, is going to be a technology war, and the US military is ill-equipped to deal with technology. It’s going to be great for tanks and guns and planes and ships, but there are going to be new things — electronics, radar, physics problems, etc — that DoD weapons labs don’t have. We need to do all the advanced weapons research outside of the military.”

The military services laughed hysterically and told the president, “Well, that’s insane.” But then, Roosevelt agreed with Vannevar Bush and set up the Office of Science Research and Development.

Bush became what we would now call the first presidential science advisor. He set up 16 separate divisions that built radar, electronic warfare, rockets, and a small physics program, which eventually spun out and became the Manhattan Project. We were the only country that did that. None of that was within the Army or Navy. The Services gave these organizations the problem sets. These civilian-run organizations built the prototypes inside of universities headed by university professors and then gave them to industry to build them at scale. That basically built the infrastructure that has kept the US ahead in science and engineering for the last 85 years.

After World War II, every university said, “You know that research and development money? We still want it.” And so, we set up the National Science Foundation, the National Institute of Health, eventually DARPA, NASA, etc., and created this ecosystem.

Now today, imagine that instead of giving those problem sets to university professors, we give them to VCs and startups. Say, “We’d like you to build weapon systems that solve these problems and/or look like this.” Not just to one or two companies, but to a suite of companies, and give them the R&D dollars to do some of the advanced things. There’s no way a startup or scale-up, of any size, is going to build aircraft carriers or ballistic missile submarines, etc. But boy, there’s a whole list of other things that really shouldn’t be inside of DoD or FFRDCs, except for maybe the exquisite sensors, the kinetic things, or interesting integration stacks.

We should think about not just reforming the acquisition process, but an ambidextrous way to think about national security. (Ambidextrous is a $20 word to describe chewing gum and walking at the same time.) The primes are essential to national security. This is not, “Let’s get rid of primes.” Or, you know, “They’re dumb.” No. They know how to do things that no startup or scale-up can. But you can’t tell me that primes can build better AI systems and deliver them more quickly than most companies in Silicon Valley. Then you could go down that list: what are the things that entities outside of the Pentagon are better equipped to do? Give them the problems. Have an organization to handle that. Have program managers managing projects outside, more like DARPA than the DoD.

We don’t have that mindset. And the reason we don’t have that mindset is that the leadership of the DoD, with maybe two or three exceptions, has never understood what the technology ecosystem looks like outside of the building. The last two who did were Ash Carter and Bill Perry, and they had some pretty spectacular results.

When you had folks who had no idea what that ecosystem looks like, we allowed China and other adversaries to move quicker than we did.

Where should founders and companies start? How can they understand what the DoD needs?

Wicker’s FoRGED Act is great. But it’s still kind of looking through the telescope backward.s

The question always is, how can startups work with the DoD? That’s asking the wrong question. The question we should be asking is, “How does the DoD reorganize itself to deal with startups?” Why aren’t we asking that question? Because if we ask that question, we then have to ask, “Why aren’t program managers fired if they’re not getting out of the building and doing technical terrain walks every 90 days or six months? What if, in fact, we actually enforce some of the rules about program managers looking at new ventures and new entrants, rather than going with old, reliable suppliers?

Today, it’s all on incumbent startups to figure out how to work with the DoD. It’s backwards. Why should a 10 or 50-person company have to figure out a 3-million-person organization? Why shouldn’t the 3-million-person organization have to figure out the thousands of startups, or how to create an ecosystem that flips that diagram?

There is a diagram of the consolidation of the defense industrial base that shows the merger of prime contractors over the last 25 years and shows how we went from ~75 plus suppliers to 5. Just visualize that and flip it horizontally—that’s what we need to create—a new generation of primes. We don’t need to get rid of those five consolidated primes, but we need to create an entirely new set of primes. Right now, it’s Anduril, Palantir, SpaceX, maybe Vannevar Labs, Saronic, and a couple of others that started in my class at Stanford. But we need to have 100s of those things starting.

Where are the DoD programs to create and incentivize that new industrial base at scale? The mindset of “Oh, here’s how you navigate the DoD,” is just completely wrong. I mean, how do you manage a dysfunctional family? It’s not like you’re supposed to navigate it. You’re supposed to get it into therapy.

I think the technical term for this is bass-ackwards.

Yeah, or FUBAR. Why are these small companies trying to navigate this complex system? The complex system is the thing that’s broken. Why don’t we fix that now?

Now what the DoD did instead is—and I can’t tell you what a disaster it is—launch over 200 innovation incubators and accelerators. I urge everyone to go read last year’s Rand report on this.

We’ve created the largest pile of innovation theater with almost zero output. Zero. The diagnostic is pretty simple. If you look at all those innovation activities, whether they’re AFWERX or Naval X, ask how many of them are tied to acquisition dollars that lead to deployment not just demos. (I’m not picking on them, they’re just the most well-known.)

If the answer is zero, if these organizations are just giving out door prizes, then you should shut them down. What they’re doing is creating culture and frustrated people, but no output.

Right now, the DoD separates innovation from acquisition. R&E and A&S are separate organizations in the Office of the Secretary of Defense and most of the services. Unless you’re doing something that’s tied to acquisition dollars, why are you creating this theater? Why are you leaving it to some poor Airman, Sailor, or Staff Sergeant to go figure out how to get an OTA or program of record inside the DoD? Instead, there should be piles of dollars or pull from the acquisition side.

When we separated R&E and A&S and redesigned the DoD in 2018, we forgot that unless we actually have acquisition dollars behind these programs, these all become innovation theater. It makes some general or Admiral feel good that we’re doing something, but it’s not producing anything that’s deployed to the warfighter at scale.

I’ll give you a good example. In the Navy, you have the Aegis destroyers, which have surface-to-air missiles to protect the carriers and the carrier strike group. One of the most innovative things the Navy did in the last couple of years regarding Aegis is basically unbundling the Aegis software and missiles from the ship, so the platform and the ship can now be separate. Great. All right, how many of these could then be deployed elsewhere? They say they have a 2045 plan to do the next 50 ships. They give you this shiny object and say, “See, look how great it is,” but it doesn’t go anywhere. But, in this case, it’s a classic example of “over Lockheed’s dead body.”

You know, Congress is coin-operated. You don’t get reelected unless you have lots of money and lots of dollars behind you. If you look at the House and Senate Armed Services Committees and appropriations committees, guess who the largest campaign country contributors are? Who has the most lobbyists on K Street? It’s the prime contractors.

Primes historically have had a lock on both influence and money in terms of what gets acquired and spent. If you don’t believe that, just look at the Major Defense Acquisition Programs (MDAP) list. There has not been a new entrant on that list in the last 30 years. And you think, how can that be, given what’s happened with technology? Therefore it’s no longer the best and most innovative weapon systems that are getting deployed. It’s those with the most influence.

This is nothing new, by the way. This has been the DoD for the last 75 years. What is new is that those technologies—drones and AI and ML, et al—are commercially available, and a good number of them are being built by our adversaries, China and Russia. Yet we’re still acting like we’re the only superpower, and therein lies the problem. We’re locked into this ecosystem we built and got comfortable with.

Defense leaders say they need more money. But I think that’s wrong. Historically, we’ve thought of the DoD budget as a zero-sum game. That is, if I want to build a hybrid fleet, then INDOPACOM needs to get rid of a carrier. But as I mentioned earlier, who’s the largest satellite manufacturer in the world? By a factor of 100x, it’s a commercial company. And while they are getting DoD dollars, the DoD did not pay for their satellite factory. Nor did they pay for a lot of other things that civilians have invested R&D in that were dual-use or could be made dual-use. The DoD has never really engaged private capital, private equity, hedge funds, whatever. They could work with Treasury to say, “Well, wait a minute, this isn’t a DoD problem. This is a national security problem that requires a whole-of-nation approach and requires some economists to actually start thinking about what kind of tax breaks we can give private equity and capital to actually invest 10s or hundreds of billions of dollars in commercial activities that could actually help the defense infrastructure.”

If you think about it, the only innovative thing that DoD has done in that area is stand up the Office of Strategic Capital and its loan authority to venture firms. But that was two individuals, Jason Rathje and Eric Volmar in the basement of AFWERX, coming up with it themselves, rather than the Secretary of Defense saying, “I need 10 economists on my staff to figure out how to make this work across the entire organization and suggest to Congress and the President how to get the entire country engaged.” Our adversaries have figured this out. China went to a whole-of-nation approach a while ago (Ash Carter first talked about it in 2015). Russia just appointed an economist as the head of their defense department. But the light bulb has not gone on yet for the US.

If you were a founder and you were looking at all of this, looking at threats around the world, how would you go about deciding what to build and where to invest your time and money?

Here’s some really simple advice. McKinsey came up with this model 30 years ago and I still like it. It’s called the three horizons model of innovation. Horizon one is making existing systems better. So, you could decide that you understand some DoD weapon systems or the problems that are addressed by existing weapon systems, and you think you have a cheaper, faster, better way to do X. If you can figure out how to work with the incumbent or convince a program manager, someone would buy that immediately. That’s an existing market.

Or, you could decide you’re on horizon two, which is taking an existing thing but repurposing it for something else. Moving Harpoon missiles onto ships or something like that. Again, you explain that to a program manager who thinks that’s interesting and you could get something going.

But the hardest ones are horizon three, which are disruptive things. For example, carriers are not going to survive within the first island chain, and maybe not the second. You don’t need to sink a carrier. All you need to do is put the flight deck out of commission. You don’t need it at the bottom of the ocean, you just need the flight deck to have enough holes in it. So maybe we need a hybrid fleet. Well, we’ve been talking about that for four years, but boy, that just breaks the mental mindset of someone who grew up wanting to be a captain of a carrier or an admiral in charge of a strike group. It’s the same with the Air Force and unmanned vehicles, right? Who wants to sit in a container in Utah when you could be in an F-35? These disruptive technologies require imagination and budgets that don’t exist. That’s where you get into the zero-sum game.

The first thing is, if you’re a startup, you need to understand which hill you want to charge. Usually, there’s money for horizon one, or you’ll be able to find it. Horizon two is harder. For horizon three, I hope you have VCs with very deep pockets and a large imagination and political influence on Capitol Hill. SpaceX, Palantir, and Anduril are examples of what I think of horizon three companies.

Start-ups also need to understand how the DoD currently acquires systems and manages their money. What the NDAA is, what PPBE is, what JCDIS is — how acquisition works. How do you shortcut that with OTAs or SBIRs or whatever? How do you become a program of record? Who are the PEO offices, etc? If you don’t understand that on day one, don’t raise any money yet. You can learn it in less than a month. It’s not an NP-complete problem, it’s not computationally unsolvable, but it looks nothing like anything you learned in business school or college or anywhere else, even if you served.

Unless you worked in acquisition, you’re not going to understand this complex model of how money moves from the government into your company, and you need to. You also need to think about what the possible distribution channels are for your product. Number one, you could be a subcontractor. You could find somebody who owns the contract or has a tribal deal, or a minority deal, and you stick on to them. There are multiple ways to get into the DoD. None of them look like anything that you’ve ever seen in the commercial world. So, hiring salespeople who understand go-to-market strategies in other commercial things is actually a detriment, because you need to unlearn every one of those things. That’s number one.

Number two is, I don’t care where your engineers are, but if your CEO does not live in Washington, DC, for the first year, you just decreased your odds again. Or you at least need a world-class office that has a co-founder in Washington. You need to be where the where the dollars are. If it’s for the army, you could maybe be with the Futures Command in Austin, or if it’s SOCOM, Tampa, but regardless, you need face time.

And then the third thing is, if you have any Chinese foreign nationals as founders, I would not start the company. Eventually, you or your founders are going to need to get clearances for most things, or at the least things that are interesting, let alone SCIF clearances.

Are there any technology areas you think people aren’t paying enough attention to?

I think a lot of the biotech stuff and life science stuff gets second duty. A lot of the DARPA-class, really wild things, like free electron lasers and other directed energy things—I just don’t see a lot of startups in that space. It wouldn’t even cost as much money as some of these big AI data center things. There is some really wacky stuff that’s probably DARPA and IQT-funded, that I should see more of in my classes or out of my founders.

Start-ups focused on hardware, esoteric material science, nuclear, and biotech, all at scale. I don’t see a lot of them, compared to the softer stuff like drones, AI, and ML. I sit on technical advisory boards for semiconductors, but I still don’t see a lot of new semiconductor startups, other than, “Here’s another GPU or inference engine.” There are also other potential places to go, like neuromorphic computing, that I don’t see enough of in startups, though I know they exist as programs inside the DoD. There should probably be much better outreach the other way around. The DoD and the service labs (ONR, AFRL, etc.) pushing harder and seeding these things all the way from university programs into a pipeline of funding, into SBIRs and OTAs. A five- to ten-year funding pipeline. You don’t see that at all.

So companies are having to figure out what to build, and you’re saying it should be the other way around, with the DoD fostering the development of critical technologies in these startups?

The telescope is inverted. As I said, it starts with leadership. When you don’t have a Secretary of Defense or a deputy who’s never worked or lived in this tech ecosystem, you think that the world ends in your five-sided building or with your primes, service labs, and FFRDCs. That’s no longer the far horizon.

That was more than sufficient for the last 75 years. It’s not sufficient now, and it’s becoming less and less relevant. It requires somebody who understands this large national innovation ecosystem and how to engage all the parties and change the people. It drove me crazy in the last administration that we were appointing the same people we would have appointed 10 years ago. Again, they weren’t stupid, they weren’t dumb, but they were no longer relevant to the issues that we needed to face, which was not how to navigate the stuff inside the building. It was, how do we integrate the stuff outside the building at the speed of our adversaries? China operates like Silicon Valley on a good day, the DoD operates like General Motors. It doesn’t work.

So far does it look like the current administration is moving in the Silicon Valley direction?

Ask me in six months.

Is all of the recent investment in defense tech a bubble? Do you think it’s going to pop?

Of course it’s a bubble that’s going to pop. I’m not a VC or an investor, but I do know that, eventually, they need liquidity. That is a fancy way of saying, they need to turn that investment into a bigger pile of money than they gave. And that requires either a public offering or generating a ton of revenue.

So far, the DoD has been a terrible customer. Its acquisition cycles don’t match the cash flow needs of startups. And who’s going to be an acquisition partner for these guys? Lockheed? They don’t pay 10x or 50x revenue. You might get bought for, like, revenue.

The problem is that the DoD has not thought about building the national security ecosystem. There would be 10 economists, as I said, in the OSD staff, worrying about this day and night. They would be obsessing over how to make a healthy and profitable ecosystem for not just VCs, but for private equity, hedge funds, etc. To get this thing operating at scale, we’d have the entire country engaged in all the parts of everything. From strategic materials, all the way to semiconductors, to every piece of technology, we’d be thinking strategically about this.

So, the answer about the bubble is just a small part of it. Go ask anybody in the OSD staff to draw a diagram of how a VC makes money. Just go give them a marker. Go to the whiteboard. Tell me how these folks make money. Now, the few that have been outside the building might have a much better inkling, but not those at the highest level, and certainly not in a way that is effective. So, how do we put our thumb on the scale? How do we get the Treasury working on this? How do we get Commerce? How do we get all the other parties?

It’s not just a DoD leadership problem, but it’s a National Security Council leadership problem. It is a presidential, executive leadership problem. No one has stepped back and said, “What do we need to do to compete against all these things?”

What do you think are the biggest threats facing the United States?

I think in the last year or two it’s our internal disunion. If you’re in the intelligence community, you understand how well our adversaries have played to our disunion and have magnified our differences internally.

The second is confusing efficiency with outcomes. We’ll see in six months whether we understand that as a country or not. That’s another version of innovation theater. So I think those are the two biggest threats. We now understand that lipstick on a pig isn’t going to fix this, and the question is, how do we fix it? Whether we fix it for real or we try to fix it with theater is what is going to make the difference.

What are your biggest red flags when looking at defense tech startups?

Any company, but particularly a defense company, requires a team. My biggest, not red flag, but yellow flag is if I have a great technologist, but no one who understands the operational side of the business. Like, what’s the go-to-market strategy for this? You invented anti-gravity. That’s great, but your idea of eye contact is whether you’re looking at your shoes or my shoes.

So number one is, do you have the right team or do you understand you need the right team and the right mix? Probably the worse version is when you think you have the right team because you have somebody who was great at selling into large organizations in the commercial world, and you think, “Oh, this is all I need.”

Not only is that the wrong team, but it will set you back because you’re going to fire that person in about six months to a year because they will make no progress.

Another red flag is not taking the time to understand how DoD is organized, how the acquisition system works, down to the detail of how you’re going to get an order. If you don’t, you need to learn it within the next 90 days. If you don’t, that’s a failure mode.

And the last pitfall is when you say, “I’ve got this whizzy object and I got a team at SOCOM really interested.” Great. Well, SOCOM, even at its best, cannot support a scalable company. They could be a pathfinder for interest in the rest of the DoD and the services. But tell me what happens after you get the SOCOM order. I’ll note, not everything needs to be a venture-scale company. Some things ought to be great small businesses.

People think, “Gee, if I get venture capital money I’m set.” Well, venture capital money requires you to deliver an obscene return to those VCs, meaning hundreds of millions, if not billions, of dollars of at least market cap if not revenue. Instead, you might decide you want to have a company that generates five or ten million a year of business. That’s not venture-fundable, but boy, if you’re dropping half of that into your bank account, that might be good enough for you. You first need to decide where in that taxonomy of innovation entrepreneurship you want to sit. I see a lot of students thinking that everything ought to be the next Palantir or Anduril. But actually, there are great small businesses that have the advantage of being a lot more agile.

Any final comments?

I’m excited that students are still excited about serving their country. On one hand, it’s been great to see the DoD investing in hundreds of accelerators and incubators which, were great for forming an innovation culture but terrible for actually delivering things. But they have shaped a common innovation language, skill set, and culture, and they have proven that there is a body of folks coming into the DoD who clearly know more about AI and ML, 3D printing, and all these things that senior leadership 20 years out doesn’t have a clue about. There’s wonderful potential that exists.

Of course, everybody in the national security space is still focused on mission, and they’re still focused on keeping the country safe and secure and deterring (and if needed winning) a war. And that’s what makes me feel great and optimistic about the country.